Mad About Bedlam

Written by Bonnie de la Hunty

24th March, 2022.

Bedlam is a word that has become synonymous with madness, confusion and chaos, but its origins are as a nickname for London’s ‘Bethlem Royal Hospital’. While Bethlem today operates as a reputable psychiatric hospital and major centre for research, its notorious history has been the subject of art and literature for centuries, including several modern horror books, films and TV series.

Robert Hooke: The Hospital of Bethlem [Bedlam] at Moorfields, London: seen from the north, with people walking in the foreground. Engraving, ca. 1750. Wellcome Library.

The History of Bethlem

Founded in 1247 as a priory dedicated to St Mary of Bethlehem, Bethlem began to be used to house the poor in the 14th century, becoming a “hospital” in the medieval sense of the word: an institution funded by charity or taxes that cared for the needy. Throughout the 15th century, Bethlehem began and then came to specialise in housing the insane, with difficult patients colloquially termed ‘stark Bedlam mad’, and poor people who pretended to be ‘lunatics’ to avoid being sent to a prison or workhouse, as ‘Tom o’Bedlams’ (MacDonald, 1981, p 122).

In 1634, Bethlem adopted a medical regime for the first time, run by a physician, visiting surgeon and an apothecary (Andrews et al., 1997, p 4), although medical ‘treatments’ mainly revolved around using physical restraint and force to control and teach good behaviour. In 1676, expansion of the hospital necessitated its rebuilding in Moorfields. The new building was designed to promote an image of grandeur and opulence to outside visitors and potential donors, since donations were relied upon (as hospitals were not yet funded by the state). The engraving below shows the statues of ‘Melancholia’ and ‘Raving Madness’ on the gates of the new hospital, thought to be the two sides of mental illness..

Camus Gabriel Cibber: A Representation of the Capital Figures of Bethlem Hospital Gate. Engraving, 1680. Wellcome Library.

It was thought that visiting to observe the phenomenon of insanity would allow one to avoid insanity oneself, but the reality is that most people were there for entertainment. Bethlem joined the London tourist trail including the Zoo, the Tower, London Bridge and Whitehall, and like those sites, crowds were biggest during holiday periods. Unfortunately, patients were not only scrutinised by the visitors, but poked with sticks, taunted, and at times physically or sexually abused. (Allderidge, 1985, p 28).

A letter from César de Saussure contains this account of his visit in 1725: “... you find yourself in a long and wide gallery, on either side of which are a large number of little cells where lunatics of every description are shut up, and you can get a sight of these poor creatures, little windows being let into the doors. Many inoffensive madmen walk in the big gallery. On the second floor is a corridor and cells like those on the first floor, and this is the part reserved for dangerous maniacs, most of them being chained and terrible to behold. On holidays numerous persons of both sexes, but belonging generally to the lower classes, visit this hospital and amuse themselves watching these unfortunate wretches, who often give them cause for laughter. On leaving this melancholy abode, you are expected by the porter to give him a penny but if you happen to have no change and give him a silver coin, he will keep the whole sum and return you nothing.” (Murray, 1902, p 92-93).

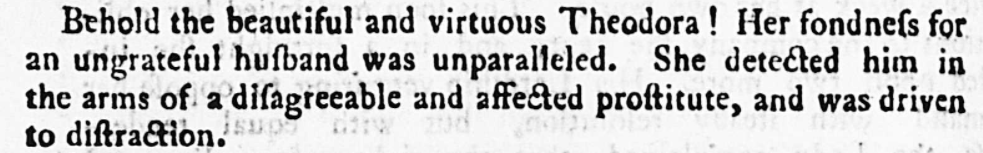

It’s worth noting that many of the patients deemed insane at this time, would not be today: the romantic portrayal of the patients in the below excerpts from ‘A Visit to Bedlam: A Vision’ in Weekly Miscellany (Goadby, R., 1774, pp 257-258), makes one question if their ‘madness’, or so-called ‘distraction’, were simply normal emotional reactions.

Bedlam in the Arts

During this same era, tales of madness, gruesome crimes of passion, and the horrors of Bedlam itself pervaded literature, theatre, visual art and music. In early 17th century Jacobean ballads and dramas like Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Macbeth, conflict often centred around which characters were mad or sane, and how easy it was to slip between the two. William Hogwarth’s 1735 play, The Rake’s Progress, is the story of a rich merchant’s son, Tom Rakewell, whose immoral living causes him to end up in Bethlem. The engraving below depicts a head-shaven and almost-naked Rakewell in one of the galleries in Bethlem.

Thomas Cook, Scene at Bedlam from The Rake's Progress by Hogarth. Engraving, 1797. Wellcome Library.

Composers of mid-17th century Restoration England such as Henry Purcell and John Eccles (whose works we will perform in our concert, Bedlam), popularised a style of song that became a genre in itself, ‘mad songs’. In these, the drama is heightened and the ‘madness’ exaggerated, in order to capitalise on the public’s interest in insanity at the time. Sudden and unconventional changes in tempi, style, pitch, and daring harmonies, portray the character as unhinged, and make for incredibly engaging and interesting music. A famous example is Purcell’s ‘Bess of Bedlam’, which is based on the poem, ‘Mad Maudlin’, which was written in reply to another, ‘Tom of Bedlam’, and narrates the story of “Poor senseless Bess, cloth’d in her rags and folly, [Is] come to cure her lovesick melancholy.” ‘Lovesickness’ causing madness is a recurring theme, and women tend to be overrepresented among the highly emotional characters.

So, how do we give a ‘historically informed’ concert of this music through a 21st century lens?

In historically informed performance practice, we use contextual research to try to understand the composer’s intentions and how their work was to be received by the audience. When performed to a modern audience, the themes will be received differently, but the same emotions and the same human connection are possible. I wrote a bit about this in my first post on this blog, ‘What does it mean to be HIP?’

The music we’ll perform in our 9th April HIP Company concert, Bedlam, is colourful, varied and exciting. The interest in madness in the Baroque era incited passionate expression in writers and composers, as they explored extremes of human emotion and embraced erratic thought patterns. It’s great fun to perform as Purcell’s erratic ‘Bess of Bedlam’, with its rapidly changing sections. Several of the instrumental pieces are examples of the hundreds based on a famous descending bassline pattern known as La Follia (‘madness’), which makes them addictively catchy to perform and listen to. We can all relate to this music in some way, because we’re all probably a little more ‘mad’ than we let on.

However, we also want to interrogate the link that has been drawn between mental healthcare and ‘madness’ throughout history, in acknowledgement of the privilege of modern education about mental health. It is now widely understood that mental illness, while affecting many, is not simply madness - it is more nuanced, varied, and serious, not a source of entertainment.

We are also reminded how much and how rapidly new knowledge can result in a paradigm shift, and therefore how much we need to keep asking questions and being open to new information. Undoubtedly we have a long way to go in changing attitudes towards mental health in today’s society, and we hope that shining light on some of this history can contribute in some small way to a world where we talk about it more and more freely.

Click the button below for information about HIP Company’s concert, ‘Bedlam’, on 9th April.

Bibliography

Allderidge, P. (1985). Bedlam: Fact or Fantasy? The Anatomy of Madness: Essays in the History of Psychiatry. Vol. 2. Tavistock Publications. 17-34.

Andrews, J., Briggs, A., Porter, R., Tucker, P., & Waddington, K. (1998). The History of Bethlem (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315002149.

Cibber, C. (1680). A Representation of the Capital Figures of Bethlehem Hospital Gate. [Engraving]. Wellcome Library. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/xtfbv4un.

Cook, T. (1797). Hogarth’s the The Rake's Progress; scene at Bedlam. [Engraving]. Wellcome Library. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/hfrudd44

de Saussure, C. (b. 1705). A Foreign View of England in the Reigns of George I & II: and the Letters of Monsieur César de Saussure to his Family. Ed. And trans. Van Mukden, M. John Murray, 1902.

Goadby, R. (1774). A Visit to Bedlam: A Vision. Weekly Miscellany: or, Instructive entertainer, Vol. 3, Iss. 63 (Dec 12, 1774), pp 257-259.

Hooke, R. (Ca. 1674). The Hospital of Bethlem [Bedlam] at Moorfields, London: seen from the north, with people walking in the foreground. [Engraving]. Wellcome Library. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/qzm69bk8.

MacDonald, M. (1981). Mystical Bedlam: Anxiety and Healing in Seventeenth-Century England. Cambridge University Press.

Ruggeri, A. (2016). BBC. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20161213-how-bedlam-became-a-palace-for-lunatics.

Whittaker, D. (1947). The 700th Anniversary of Bethlem. Journal of Mental Science, 93(393), 740-747.doi:10.1192/bjp.93.393.740.